Java JVM Memory Management

Well back in the day when I worked at Twitter, I was part of Twitter’s runtime systemst. And we were in charge of just basically making sure that all the JVMs at Twitter run without hiccups.

I did learn quite a lot about tuning JVMs for performance. I usually say that I learned quite more than I actually ever wanted to. And there’s, there’s, there’s been some hard, hard won lessons.

Typically what happens is you have your developers who write their code and when they are complete, they put it in production.

They start running it, and typically they figure out that “Oh, my God performance characteristics of this thing are not nearly as nice as we would want them to.” And that was when we came into play. That was whenthey would come to us and then we would sit down and try to make sure that their stuff actually performs.

We used to internally joke that there is this period between when developers finish the code and when it’s production ready. And that was basically us.

I don’t work for Twitter anymore. So this has been some years ago. In the meantime, I spent spent more than two years at Twitter, mostly in the JVM trenches.

I also optimize the garbage collector of the Ruby runtime as well. After that I left for Oracle where I worked on mass phone, which is the JavaScript run time on the JVM. I spoke about it last year. And as life has it, I’m actually not with Oracle anymore. I, When I circled back almost to Twitter, I’m now with this little startup called FaunaDB.

So it’s a small company. About half of us are ex Twitter employees, and we are working on creating the operational database to end all operational databases. You’ll hear about this in due time, I guess.

JVM latency optimizations

Any web services, biggest enemy is nothing else than latency.

People don’t like slow websites. They will navigate the way they want to use it. It feels, it feels sluggish and it manifests itself at the render time in the browser, manifests itself at network connections, manifest itself all the way to your service latency. And there are separate groups that deal with how can you minimize the network latency? How can you speed up the rendering on the web browser and so on and so on? That’s not my table. I deal with server side.

Normally by far the biggest latency contributor on a service that’s based on the JVM is the garbage collector.

Most of our Scala and Java based services over time by far, the biggest contributor to latency is the garbage collector. Therefore, memory tuning is crucial. If you want to have responsive applications, aside from that, you can have a in-process locking threat scheduling IO. Application algorithmic inefficiencies.

We won’t talk about those because they are not domain of tuning application. If inefficiencies can be solved by optimizations, I always different. I will talk a little bit about looking at threats, scheduling.

Maybe as far as memory tuning itself goes, you can tune for different goals and you can have different approaches to it.

Typically, ou can tune for your overall memory size. I can tune in for a memory footprint. You can tune for your application, the rate you can tune for the amount of garbage collection that your system is doing.

And I skipped slide back. When you’re talking about tuning, you can, you can tune all of these, but we will concentrate on memory. Maybe a little bit low contention. I have it in a talk. We’ll see how we fare.

As far as you want to tune your memory footprint, well, why would you want to in your memory footprint? Well, the less memory your service needs, the less pressure, there will be normally on the garbage collection. So the fastest garbage collection is the garbage collection that doesn’t need to happen.

Right. So, tuning for memory footprint is worthwhile as long as it doesn’t conflict with your other goals. Sometimes it does.

A very blatant sign that your application is using. Too much memory is obviously if you’re getting an out of memory error, I know it sounds silly and very obvious, right?

It’s also one of those things that you don’t want in production. So you would be surprised how often it does happen.

The reasons why you might get an out of memory error, or maybe I’m not getting an out of memory error, but your applications look slow because it’s, just doesn’t have a, in a memory or free memory overhead to work with.

You might just have too much data. Quite obviously.

Your data representation might be inefficient back. When I used to work at Twitter, I would typically use the word fat to refer to, inefficient memory representation. It’s a great way to evoke your mom jokes, which is also, I mean, it’s a great thing.

When you work in a company that’s mostly populated by 20 somethings.

You can also have a genuine memory leak, but we won’t discuss memory leaks. A memory leak is an application bug. So, that’s something that you need to track down and fix.

So how much memory does your application actually use? There’s a really easy way to figure that out.

I will have various GC, Flags interspersed in this, talk at times.

So if you run with verbose gc you will get a nice log output and you can observe your numbers and full GC messages.

They typically, it looks something like this. It will tell you when a full GC occurs this much memory was used. And after the GC happened, this much memory, is used now. And this is the total allocated by the JVM.

The JVM typically allocates more than what’s used and doesn’t release back to the operating system immediately because if it did that, it would have to reallocate release on every gc cycle.

And that’s plain inefficient.

So. Once it allocates additional memory tends to keep it. Sometimes it does release it though, show you how he does that. What you’re interested in is this after gc number, right? This is your live set. After GC. This amount that remains here is the live set, the full program.

And if it’s a lot. Specifically, it’s very close to either this number or it’s very close to the physical capacity of your machine. Then the obvious question is, can you give the JVM more memory? More is always better,

no performance problems or resource problems, right? most performance problems, even throughput and latency ones can quite often be fixed by throwing more memory at it.

And if the answer is yes, I can give my JVM more memory. That’s great. Give it more memory.

JVM Memory Management and RAM

All right. So. So the other question is, do you need all that data in your memory? Maybe you don’t. There are techniques for making sure that you don’t keep everything in memory.

You can use LRU caches, or you can use soft references. There is an asterisk here. I should probably make it bigger and I will talk about it.

When I joined Twitter, I thought that soft references were great, and since then I have both the Twitter and the Oracle encounter situation where soft references bit me really hard.

Basically what happens here is if you have data that can be recomputed reloaded from external sources, right? Then you don’t need to keep it in memory all the time.

Even if you loaded something in memory, you don’t necessarily have to strongly reference it all the time. Sometimes it makes sense. If it’s cheap to reload the recompute to just keep some of them in a least recently used cache and make sure that expire. So you can, you can manage your memory users like that.

So fat data is normally not an issue. These days, you just structure your classes, classes, subclasses objects have pointers to other objects. And so on most of the time, it’s all, it’s all good. Just, you know, keep to your nice object-oriented principles, structure, your code, as you would normally. But again, when you work at places like Twitter, things come like the research team comes around and they tell you, “Hey, we need to load the full Twitter social graph in a single JVM.”

We’ve been giving this guy 60 gigs of Ram and it still doesn’t fit.

Yep. Or load or user metadata in a single JVM.

So at this point, actually thinking about how can you make your internal data presentation, optics smaller. It works at these economies of scale, right? So when you, I mean, back in the day, I, I don’t remember, but this was probably.

Several tens of millions of, of graphs. And even if you don’t know, do the full social graph, just do it for active users, you will still end up with a lot. And there’s always problems like that.

So normally and this is all specific to the hotspot JVM on hotspot.

Whenever you allocate an object, it will have a header and that’s to machine words, a machine word is whatever the native size of the word on the, on the machine these days it’s 64 bits.

So whenever you allocate an object, that’s at least 16 bytes. If you want to make it sound scary, you can say 128 bits. That’s a lot, right? So you’re just doing a new Java Lang object. That’s what takes 16 bytes. One word is the class pointer. The other word is typically used for locking and some other purposes, like if they System identity hashcode, then it needs to be permanent.

Then it’s stored there, et cetera.

If you allocate an array, it’s even worse. The smallest array you can allocate is a zero, but is a zero length array of bytes. That thing will still cost two 24 bytes because we have the it’s an object, right? So you have 16 bytes for the header. You have four bites for the length of the array and six, we are on a 64 bit architecture.

You have four bites of padding until the next multiple of eight.

Padding for subclasses. If you have the simple class that only has one byte field, smallest thing, you can have this cost 24 bites because you have 16 bites for the object. Either you have one bite for that field, and then you have seven bites of padding until your next multiple of 8. If you subclass this guy, you have a think, Oh, there’s plenty of space in that padding.

So this should still 1524, right? Because 16 for the Heather, one bite for X, one bite for Y six bites of bedding. Nope.

14:00

Thing is padding happens on a subclause by subclass level. So the in-memory layout of this class. Will be 16 bytes for the Heather one bite for field X seven bites, padding one bite for Y seven bites padding.

So if you’re conscious about memory, I guess go easy on subclasses. This is a, this is a terrible advice to make.

I mean, quite often, whenever you are talking about performance some sooner or later, you will, you will find yourself at odds with nice design. So I would say. Keeps sub classes and keeps those abstraction hierarchies.

Nice if you, if you can, but if you find yourself in a situation that is biting you performance wise, then consider flattening it.

Of course, if you have a class that has a reference to another object doing something like this will immediately take away 40 bytes because, because you will have one object of C and another object.

That’s 16. And this one is 24 because it’s header plus eight bytes pointer, and similarly array elements there. No such thing as in line array elements. There’s no such thing as structs in Java yet. There’s this project while holla, which is adding value types to Java and it will be a huge boon once it’s shipped.

We will hopefully have actual value types in Java. So you could have a situation where this object is actually embedded. Well, not as an object, but there’s destruct in another.

So C programming language style structs are coming to the JVM, but until they are here, we’ll have to cope.

You can take slimming to the extreme. So remember that full of graph in memory research project at the time was referring to, we ended up there representing each Vertex, which is a user edges as int arrays because, we just couldn’t afford the pointers at that point.

It was that big. If it grew even larger. We were, I even suggested to them that, you know, you’re just linearly, scanning these arrays. We could do some variable length differential encoding in bbyte arrays. So if you, if you have objects that you need to represent like huge number of connections, say, you know, old people following Justin Bieber’s typical example of right.

But, And I actually suggested this sorta like a joke, but then being data scientists, they immediately like the idea. Anyway, as I say, don’t do this at home. This is a, this is something that you really need to resort to when, when things are going bad.

Compressed object pointers

there is such thing as a compressed object pointers, which, the JVMs typically use.

The idea is that since we are patting every address to multiple of eight, the least three bits of every point, there are zero anyway. So why not just write, shift them by three and use 32 bits. So we, 32 bits, you normally can address four gigs of memory, but if you treat every, every value as being divided by eight now, suddenly you can address 32 gigs of memory.

So the JVM actually does this quite nicely. For some reason, if you set your heap to 32 gigs, it will not use compressed pointers, but it still could, automatically uses it by until about like 30 gigs. And, if you need more than 32 gigs of heap, then you must use uncompressed pointers because with compress pointers, the max you can address is 32 gigs.

This also means that there actually exists this uncanny performance Valley, that you can’t do much about.

So there wasn’t Oracle study on very large Corpus of JBMs. That, said compressed the pointers reduced the memory load by anything between 25 to 33%. It obviously depends on the mixture of objects and your running JVM.

How many pointers do you have? But this also means that if you need more than 32 gigs of Ram, if you go to 33 suddenly, because your are not inflated you actually, your JVM will be able to store much less objects in memory. So if you need to go above 32, you need to go to at least like 42 to 48 to actually get the same amount of data that you can store in memory, same amount of objects that you can story memory.

So. 32 between 32 and 48. You don’t gain anything you actually lose because of the point inflation. So take care of that. If you see that you need more than 32 gigs of Ram, don’t go to 36 because you will actually end up being worse. There’s just a handy chart showing that how do the various, sizes and, uncompressed and compressed pointers, also 32 bits of JVMs, but nobody uses those anymore.

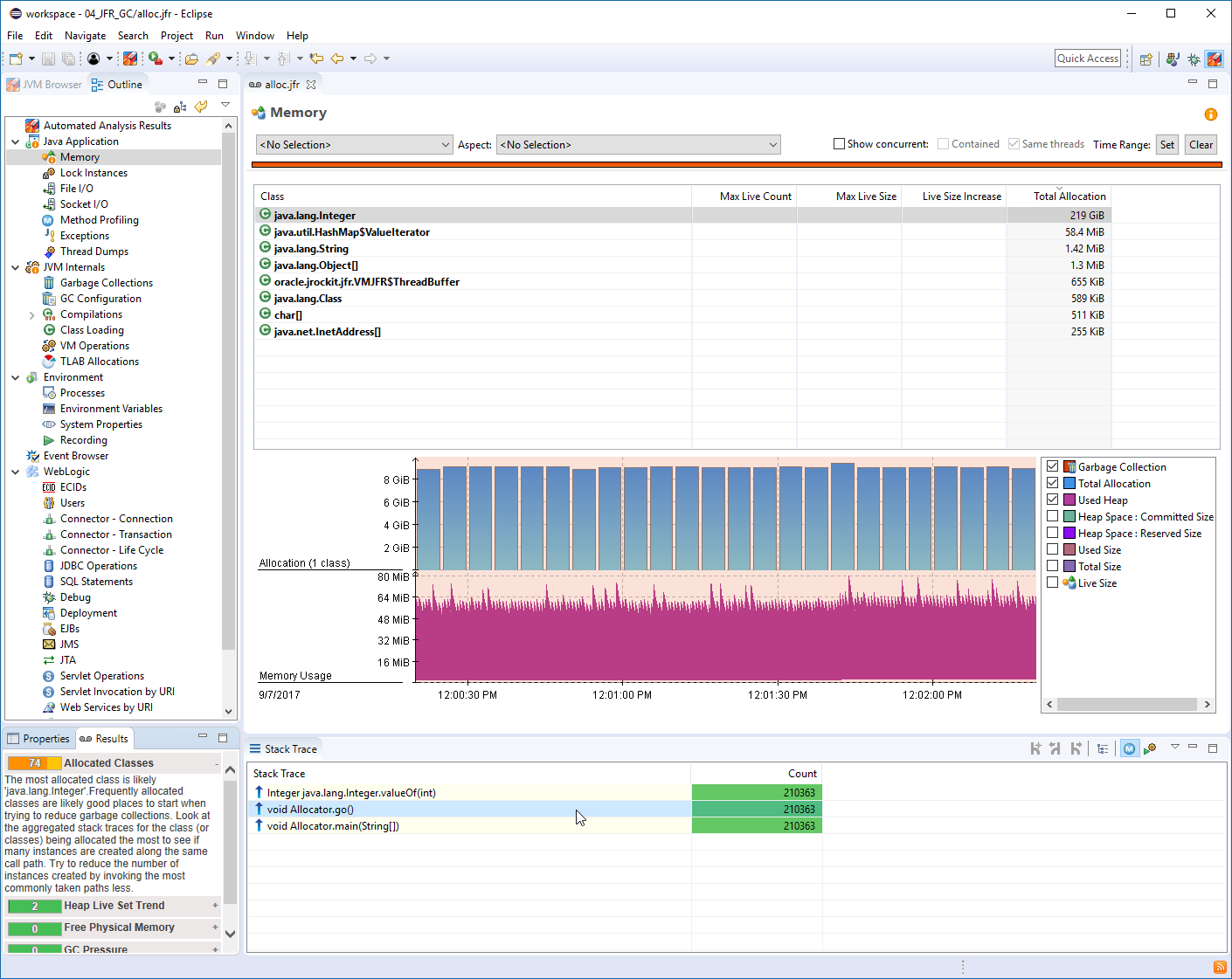

there’s some other things that you can figure out and you know, this is old, but it applies so avoid using instances of primitive rappers.

This is such a obvious and blatant thing that I’m even ashamed of pointing it out, but sometimes you don’t figure it out. So when I joined Twitter in 2010, and this is like dating, if you still use like scholar 2.7, seven and $10, like a sequence of ints we’ll use books, integers, and then re intellectually store primitives.

Now the first one. Needs this many bytes note, this, this very much factor here. And the second one obviously needs much less. And you don’t really notice this, except when you look at your program with the profiler and you see, Oh my God, w w where do all these books integers come from, then start digging and then you figure it out.

Eventually.

This was fixed in Scala 2.8, but that’s not the moral of the story I could have used any library for illustration of the concept.

The moral of the story is that you don’t know the performance characteristics of your libraries. The only way to figure out the performance characteristics of the libraries is to run an application under a profiler.

Use JVM memory profilers

If you want to optimize and tune JVM, you will need to familiarize yourself with the profilers. There’s really no way around it. Either that or read and understand the source code of every library that you rely to rely on your pick. For me personally, I would be too dumb to understand all the libraries that I rely on.

So for me, using a profiler seems like a easier way around that. speaking of libraries, there was also this funny thing with the map footprints. we used to use Google guava and it’s a great library and it has this innocuously looking very default, right? Mapmaker make map. What can be easier than that.

And it turns out this will create a map that eats more than two kilobytes of RAM, not a big deal, unless you have a problem where you need to create several millions of them, the memory. So, and obviously we had that, so, and what you can do, Oh, this creates concurrent maps. So one funny heck I did in one particular problem is I reduced the concurrency level to one to make the map.

And now it’s suddenly just to 352 bytes, and we could store about eight times as many in a memory immediately. And it was great. Now what’s the difference here?

The concurrent maps, concurrent maps are typically implemented by striping. So, striping to the number of concurrent CPU’s or course on your machine.

So th this, this can end up having 16 different stripes to increase the concurrency on V reads and writes. And if you felt concurrent to the level of one, you’d just have one Stripe. Okay. Why is it concurrent then? Right? What sense does this make? Actually, it makes a lot of sense because you still get concurrent reads.

So, I mean, compare, compare this with a synchronized map, synchronized map still, you can only have one reader or one writer in it. concurrent method, concurrency level of one can still have multiple readers, but it can only have one brighter. And the writer will also look out the readers, but still better performance.

And it’s also not sensitive to concurrent modification because the others might throw a concurrent modification, exception, this doesn’t. So we again had this thing, a service where you fan out tweets. So Twitter, third, and back then was mostly using a push model. So somebody tweets and somewhere needs to be a machine that has all of the followers of that person in a map.

And pushes it out to all connected clients. And again, if you have a very popular person that tweets something, then somewhere, you will have a larger map. And most of those maps are actually really small, but you also need to have a lot of them in a memory.

So another thing I found is, and again, just previously, my point was not about Scala. What I’m telling you now is not about thrift. Thrift is a wire format that was developed by Facebook and the Twitter is internally using a lot. It’s so you know, a bunch of microservices, they need to send data to each other and Twitter’s chosen, via format was thrift.

Thrift is pretty great because, the things that I love about thrift are also the things that they hate about thrift thrift is using a format that has no description in it. It’s very compact, but it also means that, you need generated code that can read it, from the wire because it has no self-description, you always need to have coding and decoding classes for it.

Problem is some people were using them as domain objects, which is really dumb. So here’s what happens. You have an object that named you have a class person, right? And you have a three to five format. Then your thrift coach and the rater generates you, our person class. It has a string first name, string, last name, whatever date of birth and so on.

It looks great. This is just exactly what I need. I’ll just use this. No, you don’t want to. And here’s why every thrift class that has a primitive field will also have a bit set. It has a bit sad because thrift is really thrifty on the wire. So if you say, have a Boolean field that you never set to anything, it will remember in this bit set that I never set it and it will not send it over the wire.

Now, just having this innocuous BitSight who had like seven to two bytes of overhead. To your object. Here’s why you have your thrift generated class 16 bytes, a fleece. There’s a pointer, eight bites. There’s a bit set. 16 for the Heather, another pointer to the words and other eight bytes, four bytes for the words in use, there’s an actual longer rate here, which is another 24 bytes for an array.

And then you have like a single long element here, which is 64 bits. Oh yeah. That’s the one bit that you actually use. So, and you know what, this is actually great. This, if you have a data transfer object, you don’t care about this because it only lives during the time of a, of a, of a, of a request response cycle.

And then it’s thrown away in garbage collected. But we also had some people at the company that just kept those things in memory. So they were like, I’ll just keep a thrift proxy and whatever beta ID satellites. I just keep all of this in memory. And then you got. Then you got stuck with your 72 bytes of overhead, and then of course, they come to you and they tell you, well, I have this 64 bit JVs, 64 gig JVM.

And my data doesn’t fit in Java sucks.

I went in refactor, the code, like you had opportunities for various optimizations. We had a class four location, which had like a city region, country code, metropolitan area, latitude, longitude, and so on for like Twitter’s geolocation stuff.

And then they’re just out to generate it from thrift. And so. It has so many opportunities for optimization, right? Actually you can look at the size screen size screen still. And so this was if generate them and you want to send that location over the wire, this is fine, but if you want it in a memory, you can like extract this separately.

Only have this here. It has a point or shared location. So these are already much smaller. country codes can be. Interned and, you know, sit this typically belong to a single country at the time, except in unfortunate circumstances and, and so on. And, you know, suddenly like 60 gigs of Ram went down to 20 and, you know, Java doesn’t suck anymore.

Yep. As I said, it’s not about thrift thread locals, you know what? I’ll skip this.

Latency Fighting

Let’s talk about fighting latency. So, what I was telling you about until now is various techniques for, for restructuring the program, but let’s look into it like actual latency fighting. If you were studying computer science at the university, you probably were phased with this thing where they typically tell you there’s a trade of between memory and time. Yes, there is. And this is true. It’s also overly simplified.

I typically think about this as a triangle, very novel, right? Because you still have the memory, but time is a concept that can split into either latency or throughput.

Now what you typically want to want to increase this guy? You want to decrease this guy, want to decrease this guy? also it’s mentally a little bit confusing, but you need to think about, I want to increase one, decrease the other. So, that’s why I kind of invented for my own internal use instead of memory usage.

I figured out compactness, which is higher, the less memory you use. And instead of late then CV use responsiveness, which is the higher, the less the latency is. And so what happens is that for any given. Combination of hardware operating system and your application, you will actually have some fixed cone stand, which is some kind of fi weighted to multiple of these three.

And when you are tuning, you have a fixed AE and you are trying to increase one of these. While decreasing, usually the other two, you can also optimize your code or optimize your system, which is a means of increasing the overall product. You can optimize your code by fixing algorithm, inefficiencies, throwing more hardware at it, switching to a better operating system and so on, but that’s not tuning.

That’s the difference between tuning and optimization. Yeah. normally responsiveness and throughput are at odds with each other. This is an imaginary time diagram of an application. That’s responding to requests over time. And if you optimize for throughput, you can see these guys are more densely packed, so you respond.

So it process more of them, but every now and then one of these will suffer a catastrophic GC pause. At which time it will wait until it’s. Goes further. If you optimize for latency, you typically end up with smaller throughput and each of these will incur its own little, overhead. Sometimes we have bulk applications and you want to go with this, but this is actually more preferable, especially for web applications.

It’s easier to plan for this. if you throw more hardware at the system, then you know that this would go. Lower. If you throw more hardware at a system that’s throughput oriented, it’s not really telling what will happen. I mean, it should buy you more throughput, but it’s not as clear-cut biggest threat to responsiveness in the JVM is the garbage collector.

And here here’s how typically the memory layout in a, in a JVM hotspot looks looks like you have your heap, which is split into. New part, which is even in survivor and the old park, you also have some other things like permanent generation, which went away with Java eight and caught cold cash. We are not talking about those at all.

So how does young generation work? Every new allocation happens in the Eden. It’s super cheap because there’s a point that the starts here and you allocate an object and you allocate an object in your architect objects. So it’s over just the pointer increment. It’s really fast. And when even fills up.

That’s where a stop the world copy collection happens. So all the live objects are traversed from GC routes, which has everything on stack. Everything is CPU registers and so on and gets copied in for sake of argument, survivor space one. And at that point, this pointer is just reset to zero and everything starts again.

When it fills up again, then it again is collected. Plus the. Survivor space one and everything that survived this competent to survive space too. So survivor space is the one is always empty and other is full and eventually thinks from survivor space going to the old generation. Now what’s important to note here is your dead objects.

Are free to collect. That’s why allocating is not a big deal in Java. Well, you pay the constructor price, but other than that, if the objects die, they are not even traversed here. Only the live objects are ever collected from the Eden and put in the survivor space. And then the point there is reset. So the dead objects are summarily thrown away.

Several collections, your survivors get tenured into the origin. So your young generation operation, young generation size, should it be big enough to hold more than one set of all your concurrent request response cycle objects? So if you have an HTTP server, you have 50 threads let’s suppose, and each of them needs about 10 megs of Ram to process a request.

Then you will need at least 500 megs of young sites. That’s actually a ridiculous low, but just for the sake of argument. So that all the garbage it’s created can, at least one request a response cycle concurrently go fit in it. And, you know, survivor spaces should be big enough to hold active requests.

Objects was those that are tendering. So actives maybe, or HDP request is in progress, generated four megs of garbage. It will generate another six megs of garbage, but to the point it has one mega flight objects. So it should fit in there. you have several collectors in the JVM. You have throughput oriented ones, you have Lopez ones, Lopez ones, the concurrent market sweep is a good choice for Java seven, Java eight as well, older or now use GYN GC by default.

I cannot really talk about it because it don’t matter. And so what’s really great is that if you use the throughput collectors, those guys can actually automatically tune themselves. You can tell them things like this is the maximum GC pose that I want. This is a throughput goal, and this is the ratio of time, like one to 19 that they want to spend in GC and they will try to size the memory region.

So they actually meet this goal. memory tuning is typically like rings of hell. There’s many of them and you don’t want to go too deep. This is the first ring. If you can manage it here, that’s great. Try the adaptive sizing at one place where you really want this. This is one of the Twitters queuing systems, internal cuing systems with adaptive sizing policy.

You can see it it’s pretty low. And then a lot of load gets thrown at it. Ended up the sizing policy increases the memory size. Increases it even more with than other peak, but then it, then it comes down. the ideal operation of a queue is being empty. Right? Message comes in, message goes out, message comes in, message goes out.

You want them to go. But sometimes by the nature of it, they will pile up and that’s when you need to adapt. So for queuing system throughput policy is pretty great. So if you had code box service used to put collective with no adaptive sizing for everything else to put, collectors are good with the sizing policy are a good first try.

And if it doesn’t work, then you need to use concurrent, Mark and sweep. Anything, whatever you do, you need the first junior young generation. That’s crucial. If you enable those flags, you will see a lot of interesting info in the logs. You need to. Determine your desired survivor’s size. There’s no such thing as a desire, deep in size, the more memory you can throw into Eden, the better.

There are some ex responsiveness caveats for that, but this is general advice. And. Basically the survivor size after every small little G every young GC, my energy. See, you will see that the Eden space is zero because we just collected it. So we zero it’s the most useless piece of information ever. One survivor space is always empty and another will hold some number of objects.

What’s the ideal value here? Anything below a hundred, because if this goes 200, it means that not all of your surviving new objects can fit into a survivor space. They need to go somewhere. So where do they go? They get forcibly tenured into the old generation and you want to ideally not go into the old generation.

so there’s also this interesting thing that shows you how many generations did objects survive in a, in a survivor space. You want this number to be decaying, like really decaying if, If it’s not strongly decaying, then your memory load is increasing. That means two things, a your application starting up and it’s creating all the objects, buffers, et cetera, or B you have a memory leak.

So if this is pretty constant, then you have a problem. tuning the CMS is. Again, give it a wrap as much memory as possible. the thing with CMS it’s concurrent market sweep, it’s speculative. What CMS does is your application is running and it’s allocating memory and CMS runs concurrently, right? A concurrent market sweep through ans as your program is running.

And ideally it can clean up memory faster than your application allocates it as long as it happens. You’re fine. Again, just try using CMS without tuning, just use for both GC print GCD to see whether you observe any food, GC messages you don’t. You’re done. Don’t go to the next ring of hell. If you do then go back to the young generation, then come back and tuning the CMS old generation.

You need to keep the fragmentation low. CMS does not compact. That’s one of the things that it doesn’t do normally. And. You need to avoid food. Jesus stops normally computer science. When you have two goals, they always in conflict with each other. This is probably the only time in my professional. And I figured that there was a goal that you have.

I have two goals that don’t conflict with each other. It was wonderful. And what you need to do for CMS, you need to find your minimum and maximum working set sizes. There’s a trick to doing that. You switch to a troop with collector, which only collects from the memory fields up. You see. How much did it clean, so you will observe an actual, maximum working set there and then provision this number by 25 to 33%.

So you see that your application in stable state is always 10 ma well that’s 10 gigs of Ram. Well, give it. 13 or 15 or more as much as I can’t, because as I said, the CMS needs space because as it’s cleaning replication still allocating. So we want to have extra free space for application to be able to, to allocate while CMS is trying to catch up, people will usually say, well, this man is just sitting around doing nothing.

Well, it’s not doing nothing. It’s a safety question because if your application outruns, the CMS allocates all the memory, you know what happens, stop the world. Food GC happens. And since the CMS does not compact, normally this is when it will compact. And that’s when you have like two minute pauses on large heap in a distributed system.

A two minute pause is. Indistinguishable from a host that went down, it’s that simple. So, you can do things CMS doesn’t run all the time. It, when like 80 to 75% of the memory is allocated, that’s when it kicks in and tries to save CPU. And there’s actually the flack for that. And you can actually lower that.

If you have spare CPU, you can even. Like lower it to zero. This means that basically CMS, we’re just running a sales cycle all the time in the background, in your application, if you have spare CPU cycles, that’s a good thing. Usually you have most applications. These days are IO bound. So you will typically have spare CP cyclists.

All right. and you know, if your responsiveness still not good enough, then, well, This is pretty much almost the last slide. If, you have too many live objects during young gen GC, you can try reducing new sites. This is weird. This is a weird thing that that sometimes happens at Twitter. We had the situation where collecting the young generation was taking along, but that was because we had the longest.

Lots of new objects that were surviving in that case, you actually reduce the new size, even reduce the survivor spaces, contrary to conventional wisdom. You want those to like tenuring to old generation where CMS can hopefully better handle them. And you know, it does work, but, but, but it’s weird. It always depends.

I mean, again, you need to profile, you need to watch it. And, finally, if. You can have too many threats. We had the service that had like thousands of threats, threats needs to be canned for GC because they are live routes. So you don’t need to find the minimal concurrence level that works for you. If you know, if everything else breaks, you need to break a service into several JVMs that’s.

That’s the ultimate performance tuning advice. Use more processes. Potentially more boxes, but you know, that’s, that’s, that’s literally thinking outside of the box and I think we are at time. Is that right? Okay. That’s great. Because I would have, have had a small, like part three, but that would have been another three slides with unrelated advice.

And I think that at this point, the stoke is a pretty round as it is. So thank you for your attention.

All right. Let me think questions.

Thank you for your speech. Can you please tell me, have you used of hip storage for your purposes? It seems like, uh it’s well, well it’s a preposition to use of storage. Okay. So the question is, have you used off heap storage for our purposes? Yes, with it actually, while I was at Twitter, we had the servers that was adopting Cassandra.

And, we had some Cassandra committers being employees at three, three at the time, and they were tuning it to lot and they were experimenting with off heap, buffers, they work. But the important thing to realize is that all you can store is roll bites. So you will need to take care about encoding and decoding things in your bite buffers.

And. You also don’t get any benefits of garbage collection. You need to manage those buffers on your own. In Cassandra’s case, this was workable because they were using those bite buffers as. Serialization buffers before flushing to disk. So there was a linearity to it. So you would linearly fill up a buffer and when you flush it out, it was clean.

But, we also had some people experiment with off heap storage for their own biting, coded stuff. That’s when they couldn’t make the JVM perform as well as they wanted to. And that was horrible because they ended up writing their own free lists in the bite buffers. And so on. So, yes, you can use off heap storage, but be wise about it.

if you, if you have a really good like boundaries of liveliness and preferably those are linear, then, then it’s, it’s, it’s actually a pretty good proposition. But, again, you, you will have to go back to roll, bite a raise, and then coding your data over bites. So it’s, it’s not terribly object-oriented.

Thank you for talk, from your experience in your career, what was the most craziest reason of out of memory error?

What’s the craziest out of memory error? Well, before Java eight, you have, you have permanent generation in JVMs and it can. Throw out an out of memory error as well. But what’s funny about it is that things that are kept in a permanent generation are, class data. And I had a system where a lot of classes were loaded on the fly.

So it was actually something like always GI. So versioning, something that could load different versions of the code. So what happened was that, even though we were keeping the classes in ordinary heap, the class objects themselves, Held by soft references so that the GC can clean them out whenever it needs them.

the regular heap never filled up, so they were never cleaned the permanent generation. On the other hand, it filled up. So we had this situation where the permit, we were getting out of memory errors in the permanent generation. I still had a plenty of heap. And the idea was that we are softly refer, referencing those class loaders.

They will get garbage collected when they need to get garbage collected. Except they weren’t because the garbage collection of soft reference cleaning or soft references was governed by the ordinary heap. And instead we had a out of memory error in the permanent generation. This took a while to figure out and track down because it was out of memory era, but we have plenty of memory what’s going on.

Yeah. And that was that I think that was the craziest out of memory or that they ever had was even pre-Twitter. All right. Any more questions?

Okay. Oh, that was the question

I tend to for speech. I have one question regarding to all generation and new generation you told, said, we should, But sometimes, we could pass also our object to all generation and, because we have a GC and home Depot, reducing the memory. It’s a good idea to pass whole object to alternators or better to avoid the situation.

Normally. Okay. So the question is, is it a good idea to like four subjects? If I understand correctly, the idea is, is it the good idea to force objects into the old generation? normally, no. that’s because most objects die young. That’s the so-called young generation hypothesis, and it’s been observed that for majority of the programs out there, all the objects that you create, they will die while in, in, in the young generation.

you don’t really want to, so, so ideally you want to actually keep, you want them to die while they are young and only few should tenure. So ideally in your old generation, you only have objects that are the infrastructure of your program, but anything that’s transient data request, response cycles, and so on that should ideally all just, you know, live in, live in live and live and die young.

the. When I was telling you this is that if for some reason your objects are not dying young, I’m not sure why. So your application logic is such that your objects are not dying young. Then it makes sense to make the young generation small and shove them off because. Even if you have concurrent markets sweep, the concurrent market sweep only works on the old generation.

New generation is always stopped. The world copy collected, and it’s faster. The less objects there are. But if most of those guys in Eden survive, Then it can be slow. So in that case, you might be better off just having a small, new size, making sure everything tenures, and then let CMS take care of it. But that’s unusual.

That’s an anomaly. If you, if you profile your application, you notice this trend, then it makes sense. But, but this is like counter to the normal advice, which is give as much memory as you can to the new generation. Because the more memory you give to the new generation, the higher, the likelihood that objects will die young because.

The bigger, the new generation, the definition of young becomes also larger, right? So they, they, they will be younger longer. So, so as I said, this only happens if you’re latency problems due to the minor GC collections in the new generation, we did have that. So we had an application that was tuned to the bone and still that’s some undesired latency.

And it turned out that all the latency that remained was a. Was a new generation collection latency, and we have to do something about it. So this is, this is counter intuitive, as I said, rings of hell. We were pretty much near the bottom here. Okay.

All right. Any more questions?

All right. I think we’re done then. Thank you again for.

Here are some additional videos and articles of mine (Cameron McKenzie) about Java Mission Control and Java Flight Recorder: